In 1935 Hamilton introduced the Elinvar hairspring in men's wrist watches. Elivar was introduced earlier in railroad pocket watches. The new hairspring offered more consistent timekeeping over a variety of temperatures. 1935 also introduced a new series of models with 14/0 size movements with Elinvar hairsprings, and the 987-based models were outfitted with the 987E (for Elinvar) which replaced the 987F. The F in 987F stood for Friction - as the jewel settings were friction fit instead of being held in place with screws in the original 987.

In 1936, another men's model was introduced with an Elinvar hairspring - this time with a movement used in the ladies line-up - the 989. Officially, the movement was the 989E but Hamilton's catalog just referred to it as the 989.

The Norfolk was the first men's watch in over a decade to not feature a sub-second hand. I think it's interesting that later in the 1930s Hamilton would introduce another watch without a second hand - the Contour - but that model used the 14/0 caliber with a shortened 4th wheel bit (the second hand attaches to the 4th wheel).

The Norfolk was only offered for a single year. So it begs a question - why use a ladies movement? Was the Norfolk a trial for men's watches without second hands? Did engineers realize a 980 could be modified to work instead? Beats me - but the Norfolk isn't overly rare - and Hamilton sold quite a few.

My project watch was sent to me with a description that "it would run for a while and then stop". That could mean anything when it comes to watches... maybe it's dirty, maybe it has issues. Running at all is typically a good sign but you never know. There's a big difference between "ticking" and "keeping time".

Looking at it, as received it appears to be in good shape. The case isn't overly worn and the dial has been refinished - so this watch was definitely taken care of.

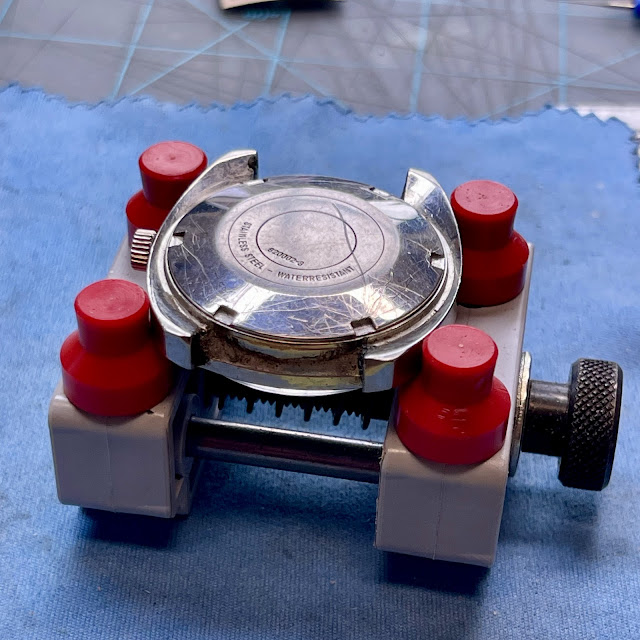

The back of the case is unremarkable - it shows just a little wear to one of the corners.

I don't normally bother checking a watch on the timer before I work on. Why bother? I'm going to take it apart anyway. However, I've learned to listen to the little voice in my head and today it was saying, "do a pre-check" so onto the timer it went.

With this model, it's hard to tell if the watch is running since there's no second hand to observe but the timer listens to the ticking. According to the display, the timer is hearing all sorts of noise - so much that it cannot even register how it's running. This shotgun pattern is never a good sign.

My first though was perhaps it was magnetized. That's an easy check - all I need to do is pass it though my electric demagnetizer. This tool generates a magnetic field. If you touch iron-based metal to the side of the tool it will magnetize it. If you pass it through the center of the field, it will demagnetize it.

No deal - although the timer is picking up a different pattern of noise now. There's something definitely going on inside this movement. We'll just have to see if a cleaning will take care of it.

The Norfolk has a two-piece case and the movement is held in the case back. With the front bezel removed you can see the dial has a light scrape in the center that extends to the 8 and what appears to be a finger print around the 6. The font for Hamilton is a little off center to my eye so this refinished dial is nothing to brag about.

The movement lifts out easily. The 1930s was an interesting period - it's the only timeframe where it's okay to not see Hamilton Watch Co Lancaster PA inside the case back. Keystone and Wadsworth cases are often seen. With any other time period you should be suspicious if the case back doesn't say Hamilton. But not today - this is a legit Norfolk. You can see the movement is a 989E, just as expected.

Personally, I don't care much for this movement design. The balance wheel sticks out like a sore thumb and it's very exposed when not in the case. One misstep and you'll break a pivot on the balance staff.

The back of the dial has a heavy coat of epoxy securing the numerals in place. The applied gold numerals have little posts that extend through the dial. When new, they are burnished in place like rivets. When the dial is refinished, the posts need something to hold them in place. Glue is a common choice.

The first thing removed is the balance assembly in order to keep it out of harm's way. Then I'll start to disassemble the remainder of the movement, piece by piece.

I'll get out my small stash of 989 movements in case I run into something.

I also happened to have two Norfolk dials... one appears to be original with a nice even patina.

The other is refinished, new-looking but without a finger print. So I have a couple of good options for this project.

Everything is cleaned and dried. This movement is much smaller than a typical men's movement and it requires a lot less space to dry. It's the same number of parts though - just a lot smaller and that makes it a little more challenging to reassemble.

The barrel bridge and train bridge are reassembled. That allows me to verify that the train wheels rotate freely before I install the pallet fork.

Everything is looking good. It's ready for the balance but I'll put the parts back on the front of the movement first - that way the balance will go on last. It's less risky that way.

I'll put the original dial on in place of the one it came with. Since the case is so nice, it's better to have a decent original dial with patina than a refinished dial with a finger print.

Okay - ready for the balance to be installed and then it's off to the timer.

Ugh... the timer is picking up the beat rate but it's running about 10 minutes fast per day. That's REALLY fast and well outside the regulator's ability to adjust.

A pass through the demagnetizer might do the trick. The demagnetizer tends to shake springs into place sometimes. However not this time. now it's running a little faster.

The beat rate is a function of several things. You could say the "balance" of the balance wheel is related to how well poised it is - perfectly weighted all the way around. But it's also related to the balance between the weight of the wheel and the length of the hairspring. Those two factors are critical to how quickly the wheel swings side to side. If the two factors are perfectly synced, you don't even need a regulator.

Regulating the beat rate is normally accomplished by moving the "regulator". The regulator has two posts that straddle the hairspring and effectively adjusts the length of the hairspring. A little shorter makes the rate faster, a little longer makes it tick slower.

However, it's possible to speed or slow the beat rate by using the timing screws on the end of the balance wheel arms. This is similar to how a spinning figure skater changes their rate of spin - they pull their arms in to spin fast and then stick them out to slow down. The timing screws on this balance appear to be screwed all the way in which is the fastest position. Perhaps someone messed with this balance? I'll see if moving them out a few turns will make a significant difference.

Well, that's a little better. I'll try again.

3.5 minutes fast per day is the best I can do with adjusting the screws. My next option is to add timing washers to slow the beat rate down. Adding weight to the balance wheel will slow the beat rate. I just need to add the same weight to each side in the same position, 180 degrees opposite to each other.

If you happened to hear an anguished cry of despair echoing over the Blue Ridge Mountains - that was me. While installing the second of two timing washers I dropped the balance about a half an inch and that was all that was needed to kink the hairspring. Hairsprings from this era are unforgiving and they are so small that only and absolute expert can make them correct again - and that's not me.

So I had to resort to one of my parts movements. After a few attempts I finally got the movement running again. This time I get 57 seconds fast per day and that's as good as it's going to get. I've pushed my luck to the limit. Did I mention I don't like 989 movements? As Shrek would say, "That'll do Donkey, that'll do".

Alright, this little 1936 Norfolk is finally running and keeping decent time for an 80 year old watch. I think the new "original" dial is a huge improvement... don't you?